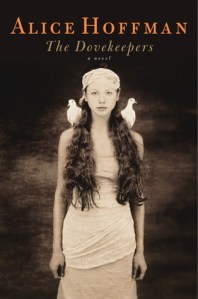

The Dovekeepers (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011) tells the tragic story of the Siege at Masada in 70 CE, when 900 Jews were trapped on a mountain in the Judean desert surrounded by an army of hostile Roman soldiers. After many months of resistance the rebels chose to commit mass suicide rather than surrender into slavery. Only 2 women and 5 children survived. They gave their testimony to a scholar named Flavius Josephus. Alice Hoffman then turned their extant accounts into this epic historical fiction.

The Dovekeepers follows the lives of four women: Yael, the daughter of an assassin; Revka, a baker’s wife who lost her daughter in a brutal Roman attack; Aziza, who was raised as a male warrior; and Shirah, “The Witch of Moab.” These four women arrive at Masada on very different paths, yet they all become dove keepers at the fortress. Shirah and Yael survive the final massacre.

Hoffman’s lengthy book is vivid and powerful, with a dramatic mix of magic and Judaism that some readers may find offensive. And some of the supernatural elements, like the cloak of invisibility, stretch the bounds of belief. Nevertheless, the book resonates with the strength of the human spirit in the face of adversity, and is a wonderful reminder of courage, sacrifice, and fortitude.

I found Shirah the most compelling character. She is an Alexandrian wise woman with uncanny insight, gifted in magic and medicine. Shirah was trained by an Egyptian priestess and passes on some of her skills to Yael. Her bravery helps the few survivors to escape through their underground cave system – the final proof of her resilience, adaptability, and cunning powers.

The Dovekeepers is a great Book Club selection, generating a lot of insightful discussion. But its length and density makes it more demanding than some other popular choices.

Copyright © 2022 | KitPerriman.com | All Rights Reserved